Hypergeometric function

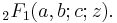

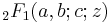

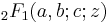

In mathematics, the Gaussian or ordinary hypergeometric function 2F1(a,b;c;z) is a special function represented by the hypergeometric series, that includes many other special functions as specific or limiting cases. It is a solution of a second-order linear ordinary differential equation (ODE). Every second-order linear ODE with three regular singular points can be transformed into this equation.

For systematic lists of some of the many thousands of published identities involving the hypergeometric function, see the reference works by Arthur Erdélyi, Wilhelm Magnus, and Fritz Oberhettinger et al. (1953), Abramowitz & Stegun (1965), and Daalhuis (2010).

Contents |

History

The term "hypergeometric series" was first used by John Wallis in his 1655 book Arithmetica Infinitorum. Hypergeometric series were studied by Euler, but the first full systematic treatment was given by Gauss (1813), Studies in the nineteenth century included those of Ernst Kummer (1836), and the fundamental characterisation by Bernhard Riemann of the hypergeometric function by means of the differential equation it satisfies. Riemann showed that the second-order differential equation (in z) for the 2F1, examined in the complex plane, could be characterised (on the Riemann sphere) by its three regular singularities.

The cases where the solutions are algebraic functions were found by H. A. Schwarz (Schwarz's list).

The hypergeometric series

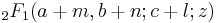

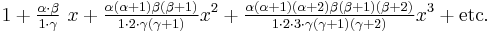

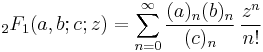

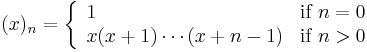

The hypergeometric function is defined for |z| < 1 by the series

provided that c is not 0, −1, −2, … Notice that the series terminates if either "a" or "b" is a negative integer. The Pochhammer symbol is defined by

For other complex values of z it can be analytically continued along any path in the complex plane that avoids the branch points 0 and 1.

Special cases

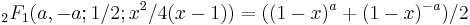

Many of the common mathematical functions can be expressed in terms of the hypergeometric function, or as limiting cases of it. Some typical examples are

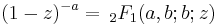

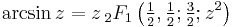

.

.

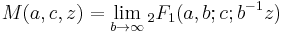

The confluent hypergeometric function (or Kummer's function) can be given as a limit of the hypergeometric function

so all functions that are essentially special cases of it, such as Bessel functions, can be expressed as limits of hypergeometric functions. These include most of the commonly used functions of mathematical physics.

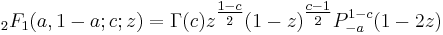

Legendre functions are solutions of a second order differential equation with 3 regular singular points so can be expressed in terms of the hypergeometric function in many ways, for example

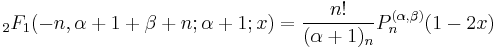

Several orthogonal polynomials, including Jacobi polynomials P(α,β)

n and their special cases Legendre polynomials, Chebyshev polynomials, Gegenbauer polynomials can be written in terms of hypergeometric functions using

Other polynomials that are special cases include Krawtchouk polynomials, Meixner polynomials, Meixner–Pollaczek polynomials.

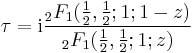

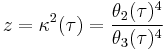

Elliptic modular functions can sometimes be expressed as the inverse functions of ratios of hypergeometric functions whose arguments a, b, c are 1, 1/2, 1/3, ... or 0. For examples, if

then

is an elliptic modular function of τ.

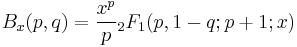

Incomplete beta functions Bx(p,q) are related by

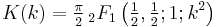

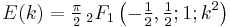

The complete elliptic integrals K and E are given by

The hypergeometric differential equation

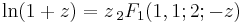

The hypergeometric function is a solution of Euler's hypergeometric differential equation

which has three regular singular points: 0,1 and ∞. The generalization of this equation to three arbitrary regular singular points is given by Riemann's differential equation. Any second order differential equation with three regular singular points can be converted to the hypergeometric differential equation by a change of variables.

Solutions at the singular points

Solutions to the hypergeometric differential equation are built out of the hypergeometric series  . The equation has two linearly independent solutions. At each of the three singular points 0, 1, ∞, there are usually two special solutions of the form xs times a holomorphic function of x, where s is one of the two roots of the indicial equation and x is a local variable vanishing at the regular singular point. This gives 3 × 2 = 6 special solutions, as follows.

. The equation has two linearly independent solutions. At each of the three singular points 0, 1, ∞, there are usually two special solutions of the form xs times a holomorphic function of x, where s is one of the two roots of the indicial equation and x is a local variable vanishing at the regular singular point. This gives 3 × 2 = 6 special solutions, as follows.

Around the point z = 0, two independent solutions are, if c is not an integer,

and

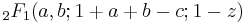

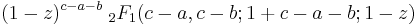

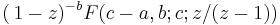

Around z = 1, if c − a − b is not an integer, one has two independent solutions

and

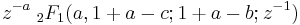

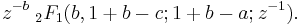

Around z = ∞, if a − b is not an integer, one has two independent solutions

and

Any 3 of these 6 solutions satisfy a linear relation as the space of solutions is 2-dimensional, giving (6

3) = 20 linear relations between them called connection formulas.

Kummer's 24 solutions

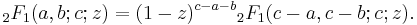

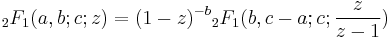

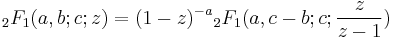

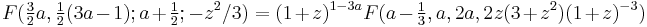

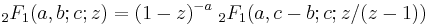

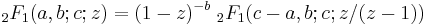

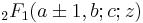

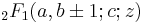

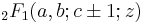

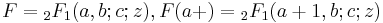

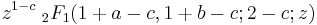

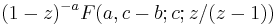

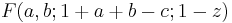

A second order Fuchsian equation with n singular points has a group of symmetries acting (projectively) on its solutions, isomorphic to the Coxeter group Dn of order 2n-1×n!. For the hypergeometric equation n=3, so the group is of order 24 and is isomorphic to the symmetric group on 4 points, and was first described by Kummer. The isomorphism with the symmetric group is accidental and has no analogue for more than 3 singular points, and it is sometimes better to think of the group as an extension of the symmetric group on 3 points (acting as permutations of the 3 singular points) by a Klein 4-group (whose elements change the signs of the differences of the exponents at an even number of singular points). Kummer's group of 24 transformations is generated by the three transformations taking a solution F(a, b; c; z) to one of

which correspond to the transpositions (12), (23), and (34) under an isomorphism with the symmetric group on 4 points 1, 2, 3, 4.

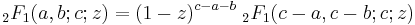

Applying Kummer's 24=6×4 transformations to the hypergeometric function gives the 6 = 2×3 solutions above corresponding to each of the 2 possible exponents at each of the 3 singular points, each of which appears 4 times because of the identities

(Euler transformation)

(Euler transformation) (Pfaff transformation)

(Pfaff transformation) (Pfaff transformation)

(Pfaff transformation)

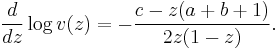

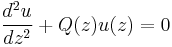

Q-form

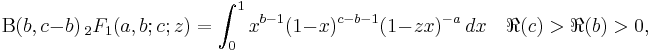

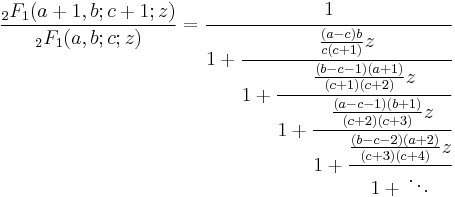

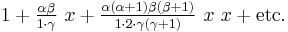

The hypergeometric differential equation may be brought into the Q-form

by making the substitution w = uv and eliminating the first-derivative term. One finds that

and v is given by the solution to

The Q-form is significant in its relation to the Schwarzian derivative.

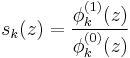

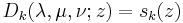

Schwarz triangle maps

The Schwarz triangle maps or Schwarz s-functions are ratios of pairs of solutions.

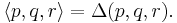

where k is one of the points 0, 1, ∞. The notation

is also sometimes used. Note that the connection coefficients become Möbius transformations on the triangle maps.

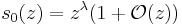

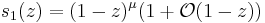

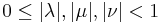

Note that each triangle map is regular at z ∈ {0, 1, ∞} respectively, with

and

In the special case of λ, μ and ν real, with  then the s-maps are conformal maps of the upper half-plane H to triangles on the Riemann sphere, bounded by circular arcs. This mapping is a special case of a Schwarz–Christoffel mapping. The singular points 0,1 and ∞ are sent to the triangle vertices. The angles of the triangle are πλ, πμ and πν respectively.

then the s-maps are conformal maps of the upper half-plane H to triangles on the Riemann sphere, bounded by circular arcs. This mapping is a special case of a Schwarz–Christoffel mapping. The singular points 0,1 and ∞ are sent to the triangle vertices. The angles of the triangle are πλ, πμ and πν respectively.

Furthermore, in the case of λ=1/p, μ=1/q and ν=1/r for integers p, q, r, then the triangle tiles the sphere, and the s-maps are inverse functions of automorphic functions for the triangle group

Monodromy group

The monodromy of a hypergeometric equation describes how fundamental solutions change when analytically continued around paths in the z plane that return to the same point. That is, when the path winds around a singularity of  , the value of the solutions at the endpoint will differ from the starting point.

, the value of the solutions at the endpoint will differ from the starting point.

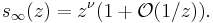

Two fundamental solutions of the hypergeometric equation are related to each other by a linear transformation; thus the monodromy is a mapping (group homomorphism):

where  is the fundamental group. In other words the monodromy is a two dimensional linear representation of the fundamental group. The monodromy group of the equation is the image of this map, i.e. the group generated by the monodromy matrices.

is the fundamental group. In other words the monodromy is a two dimensional linear representation of the fundamental group. The monodromy group of the equation is the image of this map, i.e. the group generated by the monodromy matrices.

Integral formulas

Euler type

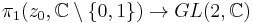

If B is the beta function then

provided |z| < 1 or |z| = 1 and both sides converge, and can be proved by expanding (1 − zx)−a using the binomial theorem and then integrating term by term. This was given by Euler in 1748 and implies Euler's and Pfaff's hypergeometric transformations.

Other representations, corresponding to other branches, are given by taking the same integrand, but taking the path of integration to be a closed Pochhammer cycle enclosing the singularities in various orders. Such paths correspond to the monodromy action.

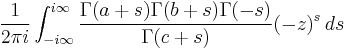

Barnes integral

Barnes used the theory of residues to evaluate the Barnes integral

as

where the contour is drawn to separate the poles 0, 1, 2... from the poles −a, −a - 1, ..., −b, −b − 1, ... .

John transform

The Gauss hypergeometric function can be written as a John transform (Gelfand, Gindikin & Graev 2003, 2.1.2).

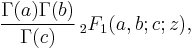

Gauss' contiguous relations

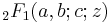

The six functions  ,

,  , and

, and  are called contiguous to

are called contiguous to  . Gauss showed that

. Gauss showed that  can be written as a linear combination of any two of its contiguous functions, with rational coefficients in terms of a,b,c, and z. This gives (6

can be written as a linear combination of any two of its contiguous functions, with rational coefficients in terms of a,b,c, and z. This gives (6

2)=15 relations, given by identifying any two lines on the right hand side of

In the notation above,  and so on.

and so on.

Repeatedly applying these relations gives a linear relation between any three functions of the form  , where m, n, and l are integers.

, where m, n, and l are integers.

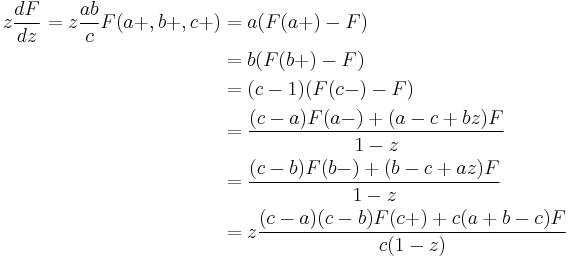

Gauss's continued fraction

Gauss used the contiguous relations to give several ways to write a quotient of two hypergeometric functions as a continued fraction, for example:

Transformation formulas

Transformation formulas relate two hypergeometric functions at different values of the argument z.

Fractional linear transformations

Euler's transformation is

It follows by combining the two Pfaff transformations

which in turn follow from Euler's integral representation.

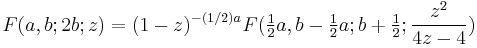

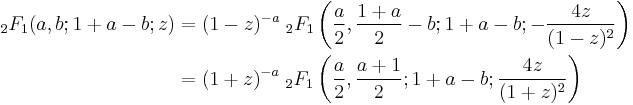

Quadratic transformations

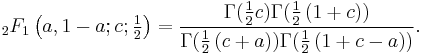

If two of the numbers 1 − c, c − 1, a − b, b − a, a + b − c, c − a − b are equal or one of them is 1/2 then there is a quadratic transformation of the hypergeometric function, connecting it to a different value of z related by a quadratic equation. The first examples were given by Kummer (1836), and a complete list was given by Goursat (1881). A typical example is

Higher order transformations

If 1−c, a−b, a+b−c differ by signs or two of them are 1/3 or −1/3 then there is a cubic transformation of the hypergeometric function, connecting it to a different value of z related by a cubic equation. The first examples were given by Goursat (1881). A typical example is

There are also some transformations of degree 4 and 6. Transformations of other degrees only exist if a, b, and c are certain rational numbers, when the hypergeometric function becomes algebraic.

Values at special points z

See (Slater 1966, Appendix III) for a list of summation formulas at special points, most of which also appear in (Bailey 1935). (Gessel & Stanton 1982) gives further evaluations at more points. (Koepf 1995) shows how most of these identities can be verifed by computer algorithms.

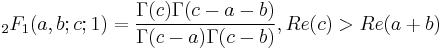

Special values at z = 1

Gauss's theorem, named for Carl Friedrich Gauss, is the identity

which follows from Euler's integral formula by putting z = 1. It includes the Vandermonde identity, first found by Zhu Shijie (= Chu Shi-Chieh), as a special case.

Dougall's formula generalizes this to the bilateral hypergeometric series at z = 1.

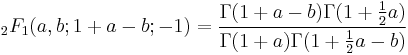

Kummer's theorem (z = −1)

There are many cases where hypergeometric functions can be evaluated at z = −1 by using a quadratic transformation to change z = −1 to z = 1 and then using Gauss's theorem to evaluate the result. A typical example is Kummer's theorem, named for Ernst Kummer:

which follows from Kummer's quadratic transformations

and Gauss's theorem by putting z = −1 in the first identity.

Values at z = 1/2

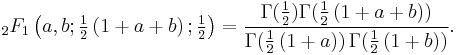

Gauss's second summation theorem is

Bailey's theorem is

Other points

There are many other formulas giving the hypergeometric function as an algebraic number at special rational values of the parameters, some of which are listed in (Gessel & Stanton 1982) and (Koepf 1995). Some typical examples are given by

Generalizations

Generalizations of the hypergeometric function include:

- Appell series, a 2-variable generalization of hypergeometric series

- Basic hypergeometric series where the ratio of terms is a periodic function of the index

- Bilateral hypergeometric series pHp are similar to generalized hypergeometric series, but summed over all integers

- Elliptic hypergeometric series where the ratio of terms is an elliptic function of the index

- Fox H-function, an extension of the Meijer G-function

- Generalized hypergeometric series pFq where the ratio of terms is a rational function of the index

- Heun function, solutions of second order ODE's with four regular singular points

- Horn function, 34 distinct convergent hypergeometric series in two variables

- Hypergeometric function of a matrix argument, the multivariate generalization of the hypergeometric series

- Lauricella hypergeometric series, hypergeometric series of three variables

- MacRobert E-function, an extension of the generalized hypergeometric series pFq to the case p>q+1.

- Meijer G-function, an extension of the generalized hypergeometric series pFq to the case p>q+1.

References

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1965), "Chapter 15", Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, New York: Dover, pp. 555, ISBN 978-0486612720, MR0167642, http://www.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_555.htm.

- Andrews, George E.; Askey, Richard & Roy, Ranjan (1999). Special functions. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. 71. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62321-6; 978-0-521-78988-2. MR1688958.

- W. N. Bailey Generalized Hypergeometric Series Cambridge 1935

- Frits Beukers, Gauss' hypergeometric function (2002) (Lecture notes reviewing basics, as well as triangle maps and monodromy)

- Daalhuis, Adri B. Olde (2010), "Hypergeometric function", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F. et al., NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521192255, MR2723248, http://dlmf.nist.gov/15

- Erdélyi, Arthur; Magnus, Wilhelm; Oberhettinger, Fritz & Tricomi, Francesco G. (1953). Higher transcendental functions. Vol. I. New York–Toronto–London: McGraw–Hill Book Company, Inc.. ISBN 978-0-89874-206-0. MR0058756. http://apps.nrbook.com/bateman/Vol1.pdf.

- George Gasper and Mizan Rahman, Basic Hypergeometric Series, 2nd Edition, (2004), Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications, 96, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-83357-4.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1813). "Disquisitiones generales circa seriam infinitam

" (in Latin). Commentationes societatis regiae scientarum Gottingensis recentiores (Göttingen) 2. http://books.google.com/books?id=uDMAAAAAQAAJ. (Gauss's original paper can be found in Carl Friedrich Gauss Werke, p. 125)

" (in Latin). Commentationes societatis regiae scientarum Gottingensis recentiores (Göttingen) 2. http://books.google.com/books?id=uDMAAAAAQAAJ. (Gauss's original paper can be found in Carl Friedrich Gauss Werke, p. 125) - Gelfand, I. M.; Gindikin, S. G.; Graev, M. I. (2003) [2000], Selected topics in integral geometry, Translations of Mathematical Monographs, 220, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2932-5, MR2000133, http://books.google.com/books?isbn=0821829327

- Gessel, Ira & Stanton, Dennis (1982). "Strange evaluations of hypergeometric series". SIAM Journal on Mathematical Analysis 13 (2): 295–308. doi:10.1137/0513021. ISSN 0036-1410. MR647127.

- Goursat, Édouard (1881). "Sur l'équation différentielle linéaire, qui admet pour intégrale la série hypergéométrique" (in French). Annales scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure (Sér. 2) 10: 3–142. http://www.numdam.org/item?id=ASENS_1881_2_10__S3_0. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- Klein, Felix (1981) (in German). Vorlesungen über die hypergeometrische Funktion. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften. 39. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-10455-1. MR668700. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?PPN375394591.

- Koepf, Wolfram (1995), "Algorithms for m-fold hypergeometric summation", Journal of Symbolic Computation 20 (4): 399–417, doi:10.1006/jsco.1995.1056, ISSN 0747-7171, MR1384455

- Heckman, Gerrit & Schlichtkrull, Henrik (1994). Harmonic Analysis and Special Functions on Symmetric Spaces. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-336170-2. (Part 1 treats hypergeometric functions on Lie groups.)

- Kummer, Ernst Eduard (1836). "Über die hypergeometrische Reihe

" (in German). Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 15: 39–83, 127–172. ISSN 0075-4102. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?GDZPPN00214056X.

" (in German). Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 15: 39–83, 127–172. ISSN 0075-4102. http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?GDZPPN00214056X. - Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007), "Section 6.13. Hypergeometric Functions", Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8, http://apps.nrbook.com/empanel/index.html#pg=318

- Slater, Lucy Joan (1960). Confluent hypergeometric functions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. MR0107026.

- Slater, Lucy Joan (1966). Generalized hypergeometric functions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06483-X. MR0201688. (there is a 2008 paperback with ISBN 978-0-521-09061-2)

- Wall, H. S. (1948). Analytic Theory of Continued Fractions. D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc..

- Whittaker, E. T. & Watson, G. N. (1927). A Course of Modern Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Yoshida, Masaaki (1997). Hypergeometric Functions, My Love: Modular Interpretations of Configuration Spaces. Braunschweig/Wiesbaden: Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn. ISBN 3-528-06925-2. MR1453580.

External links

- The book "A = B", this book is freely downloadable from the internet.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Hypergeometric Function" from MathWorld.

![z(1-z)\frac {d^2w}{dz^2} %2B

\left[c-(a%2Bb%2B1)z \right] \frac {dw}{dz} - abw = 0.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/beec33f8481a77541d85471f945cf284.png)

![Q=\frac{z^2[1-(a-b)^2] %2Bz[2c(a%2Bb-1)-4ab] %2Bc(2-c)}{4z^2(1-z)^2}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e795215108356959508f0fd0c79bc8a3.png)